Tutkimushanke Isolammen metallidetektoritutkimus

TakaisinPerustiedot

-

Kunta:Tampere

Vanha kunta:Messukylä

Nimi:Isolammen metallidetektoritutkimusHankkeen tyyppi:Arkeologinen inventointi

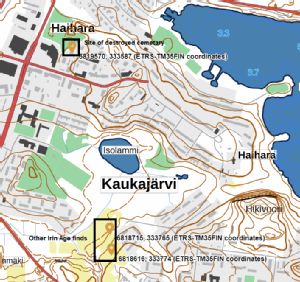

Hankkeen lyhyt kuvaus:A metal detector survey of part the North-west section of Isolampi, a small lake/pond in the Messukylä district of Tampere. The survey is to be conducted in 2 stages. The first detector survey on several sections of the lakeside shoreline, the second stage being an underwater metal detector survey of the lake, an area of some 50m x 50 m, adjacent to the area on land surveyed.The aim of the study was to ascertain if there were any archaeological finds or cultural worth near or actually in this part of the lake. This was the closest body of water to the large Iron Age cemetary discovered and excavated at Vilusenharju, Messukylä in the 1960s, and now built over with modern housing. The hypothesis is that there was a possibility that Iron Age ritual deposition of objects, particularly metals, may have occurred here, as the cemetary site was less than 400 metres away. There have also been a few Iron Age finds several hundred metres to the south of Isolampi, with the possibility that the north-west and west side of the lake may have been a regular trade or travel route, and increasing the likelihood of other finds.

In the first stage on land 3 small areas were inspected with the metal detector over a 50m wide stretch. Survey areas were recorded using tape measures and GPS. All hits were recorded and ground-truthed. Various iron objects were discovered, recorded, and removed to Pirkanmaa Maakuntamuseo. They were found to be either parts of modern fencing that was put up when the northern lake path was built in the last 30 years, or to be of indeterminate function and likely modern, or various pieces of drainage tile, likely to have been built recently to take excess water from the waterlogged peat soils under the path and to drain into the lake.

Vastuutaho/vastuuhenkilö:David Cleasby, in cooperation with Pirkanmaan MaakuntamuseoHankkeen alkupvm:07.12.2019Hankkeen loppupvm:10.10.2020

Tekstitiedot

-

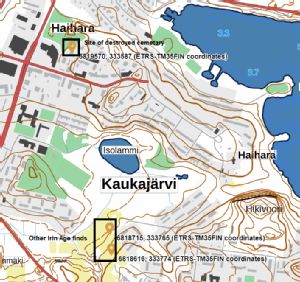

Johdanto:This project had several aims. Foremost it was to establish if the Isolampi area was an area of cultural significance, particularly for the Late Iron Age. Secondly, to determine whether there were any connections to the Late Iron Age cemetery discovered in the gravel pit quarry at Vilusenharju ridge in 1961, and excavated for a further 10 years, and which has provided the richest collection of Iron Age finds for the whole Pirkanmaa region, and arguably for Finland (See Photo 2). Cremation graves as well as 50 body graves were discovered and over 3000 objects, including jewellery, silver handled swords from Germany, textiles, coins from Britain and the Arab world, and 2 crosses, among many other items, with the whole site in use from around 900AD to early 1100s (See attached Vilusenharju finds pdf and reports, and summarised below). There are various estimates for the cemetery size ranging from 4,500 square metres up to 11,500 11,200, since it is hard to be sure as it was discovered in the middle of a gravel extraction process which started in the 1940s, and by the time archaeological excavation was carried out in 1961-2 much of the site had already been destroyed. After the last investigations in 1971 the extraction process continued. Later the area was turned over to housing construction.

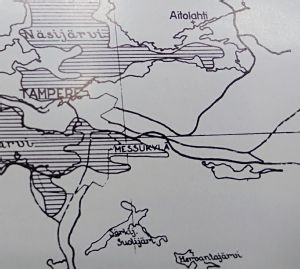

Estimates of how close the cemetary was to the small lake or 'Lampi', best translated from Finnish into English as a large pond, vary from 400 to 500 metres depending on estimates of the size of the cemetary. However, as there has not been a residential site identified, associated with the cemetary, there may well have been Late Iron Age cultural activity closer to Isolammi. Certainly it seems likely that the gravel ridge geological feature that extended from Kaukajärvi to the east, and all the way to the centre of modern Tampere, to Pyyniikki ridge and then beyond, was actively used in the Finnish Iron Age, probably for offering hard ground and an elevated vantage point. The excavations in the 1960s suggested that there was a definite road of sorts running along the ridge, and possibly passing by and overlooking Isolammi. Links to the excavation finds are included in the Links section below.

Perhaps of relevance, there were 2 Iron Age finds made some 400 metres south of Isolammi, and 850 metres from the cemetary. In 2013 in a field called Juva 15-20cm deep in clay soil the strut of a belt divider was found, and then subsequently a pendant and a diamond-shaped piece of a shield. The field itself seemed to be rich in molten metal, probably bronze). In another site nearby an Iron Age ring was discovered and a wrist pendant (See Photo 2 for their position as well as details in 'Lähteet' section). Isolampi sits halfway between the cemetary and these 2 sites forming a possible connective route between these sites, the western edge of the lake and the cemetary, although the lack of dating evidence does not allow the possibility to narrow down the timelines sufficiently.

The lake itself was selected for study not just because of its reasonable proximity to other sites, but for several other reasons. Bodies of water, such as seas, lakes, and rivers have often been discussed in archaeological theory as places not just for recreation, fishing or mediums for trade and communication, but also as sometimes having an element of ritualistic practice for some past societies. This could potentially manifest as items deposited in water as some sort of funerary ritual, or as an offering to whatever religious belief that was held, with previous studies of Iron Age sites in particularly the UK and Denmark as potential indicators of a widespread phenomena. It is possible that bodies of water could provide one of possible many causal factors for the siting of cemeteries, or habitation sites that could have led to cemeteries being built nearby. Roughly 50% of burials from the Finnish Iron Age seem to occur in close proximity to lakes and rivers, with many overlooking bodies of water, often on small peninsulas, with water on 3 sides, or on islands (Wessman 2010). Certainly there seems to be a strong correlation of Lapp-Cairn burials to bodies of water in the Early to Middle Finnish Iron Age, although the relationship of burials to water seems less apparent in the Late Iron Age, with less sites overlooking or close to water, or the distances becoming so great as to become less clear a meaningful relationship (Saipio 2018). The nature of the relationship of burial sites to bodies of water is a complex subject, and requires far more research, and would seem to vary considerably across time, which is logical as burial practices seem to change also. The geographical abundance of Finnish lakes, ponds and rivers, especially in Central Finland, may well mean such relationships are more haphazard then meaningful. The distance of 400 metres from the cemetary may also reduce the potential for cultural finds.

The third reason for selecting this site was to provide a practice area for developing a maritime archaeological approach to the cultural landscape, specifically to improve personal methodology for studying small lake sites. Considering the large numbers of Finnish waterways it seems logical to view the environment not just from a land perspective, but a water perspective. Therefore, both the foreshore of the pond and the adjacent water were selected for survey. In regard to the second stage of the project where the researcher would enter the water, the shallow and silty waters of this type of small lake, especially when investigating the shallower sections of the pond, was expected to provide considerable challenges. The edges of the pond were about 1-1.5 metres in depth which was too deep to investigate with wading boots, or a dry suit with a snorkel, but quite shallow to make scuba equipment effective. It was also expected that once the metal detector found an item, the disturbance of the clay and silt layers might make visibility very difficult.

The last aim was to provide practice for using an underwater metal detector in a relatively benign site, where coverage of the underwater area could be achieved quickly and safely.

The land survey is recorded in this report and an underwater survey will be added once that fieldwork has occurred.

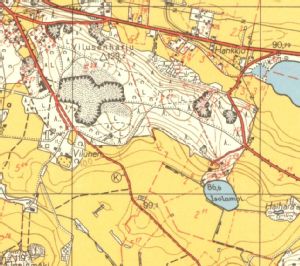

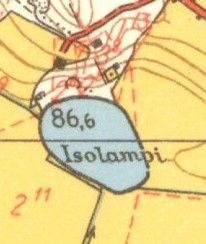

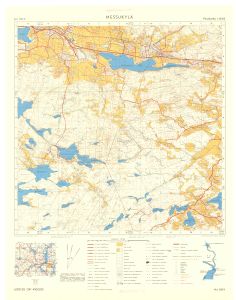

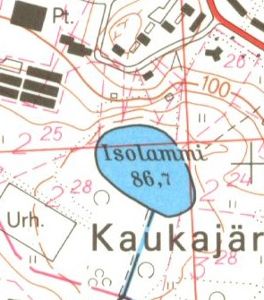

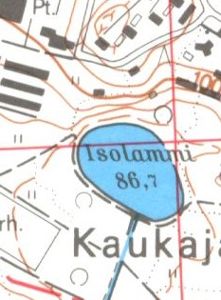

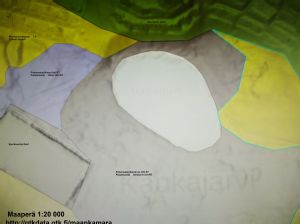

Hankealue:Isolampi itself is 200 meters long, 150 meters wide and covers an area of 2.2 hectares. Isolampi is located in the middle of the Kaukajärvi district surrounded by parks and residential areas, and sits in the middle of woodland. The shoreline of the pond is 550 meters long and its shoreline is surrounded by interconnecting paths. This area of woodland preserve is surrounded to the north and west by housing developments, and to the south and south west is meadow land, some of which has been given to recreational use.Topographically the most obvious feature of the area is the ridge to the north and north west of the lake, which has sharp inclines and rises from 87mpi at shore level to 117 mpi at the highest point, some 170 m north.Coordinates for the lake centre are N = 6819098,000, E = 333815.000.

The lake itself is 86.7 metres above sea level, maximum 6.4 metres in depth, and mean depth 2.41m.

The area selected for survey on land was a 50m wide stretch of foreshore on the north-west corner section of Isolampi, and stretching some 50 metres back inland from the water's edge. On practically the whole north side of Isolampi is a steep hill, but on the north-west corner the ground flattens out. If the topography has not been substantially altered in the last 1000 years then it seems if persons were to approach Isolampi from the general direction of the cemetary then this would be the most likely point. There are modern footpaths that seem to use this flattening of the contours to allow allow people to descend from the ridge safely to the lake. A grid was laid out and anchored to small permanent concrete blocks that had been laid by modern engineers around the water's edge. From these points 2 areas for metal detector survey were laid out these at the north-west edge from the waters edge towards the modern path, which was some 7-8 metres from the water's edge.

A further survey area was taken more on the northern edge and taken from the water's edge back some 50 metres up until the edge of the sloping contour. The terrain from the path towards the hillside was boggy, consisting of peat, and there were trees that seemed relatively young and purposely planted in rough rows in modern times. The presence of peat was seen as an indication that this area may have been flooded for a long time in the past and been part of Isolampi. It raised the possibility that the water's edge came up to the bottom of the steep slope, or even reached higher up the contour. Therefore the survey was extended up to bottom of the slope, following the theory that if objects were to be deposited into the water they could be dropped from the top of the steep slope, or following the possibility that objects may have tumbled down the slope with gravity by natural process. Modern houses had been built at the top of the slope with no indication from the construction records that there had been signs of previous occupation.

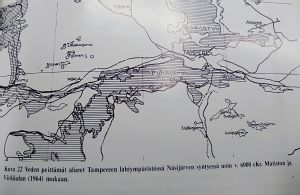

In geological terms, the sand, rock and gravel ridge to the north of Isolampi was left after the last ice glacier retreated around 9000 BC, experiencing considerable post glacial uplift, which is still occurring at around 2mm a year, and producing the prominent ridges that extend all the way from Kaukajärvi through modern central Tampere and onto Hämeenkyrö. The sand deposits in the ridge originated from deposition processes when the Baltic Sea poured in after the glacial retreat, and which then experienced the uplift. Around 6000BC the area of what is now Messukylä became flooded when Lake Näsijärvi burst its banks, creating the Tammerkoski rapids, and spilling eastwards, forming a water corridor through Lidesjärvi and almost as far as Kaukajärvi, and therefore forming Isolampi as a consequence. Geological maps show the area around Isolampi experiencing peat layering, and highlighting a long-term process of vegetation and tree decomposition. There are also fluvial deposits to the west of Isolampi, perhaps caused by the initial flooding process caused by Lake Näsijärvi bursting its banks. There is no sign of a watercourse there now.

There were no studies found of the geology and organic makeup of Isolampi itself. It was shallow, max depth 4.1m, with c. 1m depth at the edges. There are no obvious tributaries in and out of the pond so the water balance was relatively constant, experiencing some evaporation in summer and water addition via snow in the winter. It It experiences runoff from the slopes above to the north. Comparisons can be made to Lidesjärvi to the west (Alhonen 1081), as the lake is also around 4m, but some of its internal mechanisms will vary considerably, as it was connected to other streams and rivers to both Pyhäjärvi and Kaukajärvi. Lidesjärvi water has a brownish tinge, has a high phosphorous content, and considerable oxygen deficiency. It also has a high nutrient level resulting from sewage, which Isolampi may lack, so that plankton there are probably similar to Isolampi but not the same. The soil layers comprised a mixture of organic brown detritus, from leaf and tree decomposition, sulphide bands and pale grey clays. On first inspection Isolampi seems very similar, with bottom conditions so anoxic as to allow little plant or animal life.

No records were found that indicate definite human activity in the area of Isolampi itself, although as stated some Late Iron Age finds were discovered some 400 metres south. The extent of the peat layers suggest that the water once covered a wider area, and either has shrunk naturally, or been subject to deliberate human re-landscaping, such as marsh reclaimation, although it is known that studies of Lidesjärvi indicate that there was some degree of peat management as a fuel source (Alhonen 1981, p36). Certainly, the area now called Messukylä experienced considerable human activity in the Middle to Late Iron Age, with a cross coffin and other small items found in Kukkoinkiven cemetary from 600 to 800 AD, finds at Veijanmäki cemetary from 800 AD to around 1100 AD, and nearby to Isolampi at Vilusenharju cemetary around 1000AD. The settlement of Takahuhdi became the largest village in Messukylä by the 14th century at the latest, when the name Messukylä was first mentioned in 1439 in reference to the chapel parish.

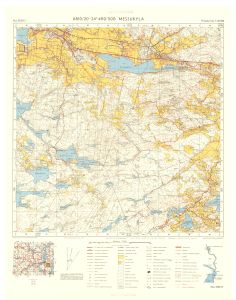

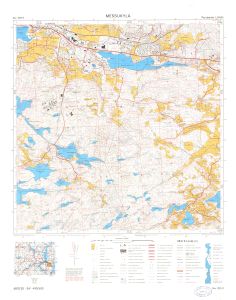

Maps have been included in the photographs section showing the general development of the area from 1783 onwards, and to act as a simple gathered resource for future researchers of this area. The maps of 1783, 1840, 1907 and 1936 indicate that the pond was circled by woodland, with meadows to the west, and no buildings to speak of. The 1953 maps show a sharp contrast to before with the extent of the gravel pits clearly indicated and clear paths extending west-east along the ridge, and particularly one to the area just above Isolampi. The closeup shows a few buildings on top of the ridge but little else. The 1960s maps show the reasonable proximity of the pond to the newly discovered cemetary site, surrounded by the gravel pits. The immediate Isolampi area still seems relatively untouched. By 1975 the gravel pits seem to have destroyed the site where the cemetary was, while to the south a sports centre has appeared, and several housing units to the west and north. By 1991 the gravel pits have disappeared in the area where the cemetary was and housing units seem to have grown in number, while in the immediate vicinity of the pond a footpath has been built around its west and south side. By 2020 there are overall more housing but the general area of Isolampi has been kept as a recreational nature spot. The biggest change has been a footpath built around the north side, so walkers can circumnavigate the pond (See the 2020 maps). 2 other maps from the Peruskartta have been attached to emphasize the natural environment in terms of vegetation and topography.

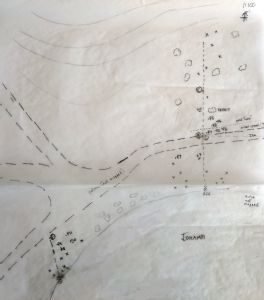

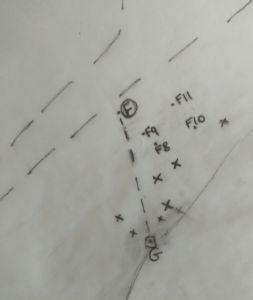

Aikaisemmat hankkeet:There are no previous archaeological projects in this area.Menetelmät:2019 Metal detecting on the foreshoreThe project employed 2 different stages. The first described here involved picking areas on the foreshore where it seemed more likely Iron Age people may have deposited items, if indeed Isolampi had been a site at all. The concrete square blocks, marked 67, 66, and Suomi, provided permanent datum points and could be used to establish a grid. In fact some of them even had metal pins on the top allowing good accuracy to the centre of the blocks. From these points and the grid, where the detector identified hits measurements could easily be taken from the laid down survey tapes, recorded, and added to a plan later if finds were discovered. GPS readings for all the points were taken, with the intention to do the same for obvious cultural finds with historical value, but not for each hit, or mundane object.

3 main areas were identified as starting points, to be expanded if finds warranted it. The first area was at the north northwest edge of the small lake, near point 66, renamed A. A corridor was formed for the survey that stretched from the waters edge across the path area and right up to the edge of the steep slope. Therefore the search might hypothetically find objects deposited at the current waters edge, as well as beneath the slope where it was possible the edge of the water may have been in ancient times, there being no previous maps or surveys to establish exactly where the waterline was. The second area was to the west of point A nearer to the waters edge and following the pond's curvature. The third area was 20 metres away, exactly where the path to Isolampi from the west hit the water, as a possible closest access point for humans to the water.

The metal detector, a Garrett Sea Hunter Mark 2, was selected as it would allow underwater as well as land use. It was set at its lowest elimination setting so it would pick up all iron objects, the main objective to look for items from the Iron Ages, and not looking for precious metals as treasure hunters might. It was used in a sweeping motion covering 1-1.5 metres. Where a hit was made the space would be marked with a metal pin, and the search continued until several other hits were made. Then the researcher could dig for a while in all those areas to find the hit's origin. The theory was that this would allow faster detecting and digging. If there were 2 researchers 1 could detect while the other dug, thus limiting the time taken to keep taking the equipment on and off. With 1 researcher it would seem to save time.

Hits with the detector, where the object found was so small or unidentifiable, as well as where no finds were discovered were marked as an X on the map and obvious objects recorded as finds. If an hit occurred in a spot then it would be dug deeper until no further hit occurred. Finds discovered were labelled, kept moist if taken from the peat, and removed to the museum for final identification. The usual post analysis, recording of finds, map drawing and dissemination into the Pirkanmaa 'Siri' database would then occur. It would then be decided it further studies of that type would be warranted there.

In regards to safety on site, since the work was carried out near water and around a public footpath, the team comprised of pairs to assist and monitor each other, high visibility jackets were used, a safety rope was available if someone fell in, all trip hazards were minimalised, and first aid kit taken on site. The research team carried permission letters from the museum, and spent considerable time explaining the aims of the project and possible interesting knowledge and benefits to the area if the research proved fruitful.

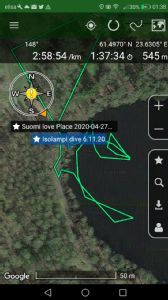

2020 Dive survey

A team of divers set out to perform a metal detector survey of the west and north-west sections of the lake. Tracks of the lake would be recorded by a GPS device floated on the surface. One of the divers would carry a reel and allow a circular search of the lake, with ever increasing circles. Where metal detector hits occurred the lake bottom would be gently dug to extricate the object, while minimalising the amount of silt displacement, and its nature and position recorded by another diver. Finds were to be recovered only if considered significant.

Tulokset:2019 Shore surveyIt became clear that the process would be slow as there were many targets found with the detector that provided metal objects too small to identify, or no objects at all distinguishable from small pieces of grit, and complicated by the fact that all the objects had the same colouring as the soil and pieces of grit, especially in the peat areas between the path and the slope.

There seem to be 3 separate 'zones' in each location

- the first between the waters edge and the gravel path

- the second being the gravel path which was some 20 cm deep, with indications of concrete infill underneath and on either side, to resist the movement and drainage of peat towards the lake, and keep the path totally solid and dry. The depth of the path and whatever hardcore infill lay beneath indicate considerable destruction of potential finds, certainly any intact features.

- the third being the peat layers beyond the path. Here was found the 'modern' fencing and the nails, which may suggest that the area was fenced off by the construction workers, while the path was built, and then partly allowed to sink into the peat afterwards.

It is clear that no metal finds were discovered of archaeological significance. This was expected under the gravel path, and immediately to either side, but the absence of any other finds near the water's edge or on the peat layers, seem to indicate this area was of low value. However, it was still only a small sample area, and future research may occur on the foreshore if conditions change, such as material found underwater at a later date.

In regards to the method, several lessons were learned.

1. The use of permanent datum points was essential so the site could be visited on several occasions with repeatable accuracy. This was born out even more so as the GPS readings taken for the points were some 2-3 metres out when analysed, and when repeated did not give the same results.

2. Following from point 1, the use of more professional Sat Nav equipment was required for similar projects, and not 'Maastokartta' run on a mobile phone. In this case the fact that the permanent concrete blocks showed on the engineers map, and were likely to be permanent features, allowed certainty that these areas could be found again with accuracy, and that future surveys would know to avoid these areas if new coverage was sought.

3. The use of tapes, datum offsets and trilateration proved effective for accuracy in this case, as identification of the initial value of an area was the issue at hand, and not a detailed excavation of a specific feature.

4. The basic strategy to dig at the north west and northern end of Isolampi, depended to a large extent on the actual position and margins of the lake in the past, not just now. It is unknown if the lake was wider and extended 10-20 metres further north to the bottom of the slope. The presence of peat there over 40cm in depth could be viewed several ways. It could suggest that that area had been waterlogged for centuries and was originally an area of soil, that gradually flooded and slowly became peat. It could also have been water in the Iron Ages and has turned into peat over the last 1000 years. It could be that the peat surface there was produced with more modern landscaping, However, the last theory seems unlikely as all the maps from 1783 until the present and the surrounding features seem to give the same shape for Isolampi and other features without obvious change. The building of the gravel path, the presence of the fence, and the planting of trees in rows in the 1990s or so, would seem to be recent changes confined to the area of the path development, and the peat surfaces in the remaining 15m to the slopes were different to that. What would be needed is an in-depth geological assay which analysed soil components and any organisms included. However, this would not be warranted because of the absence of important finds.

5. In regards to metal detecting, this model was extremely sensitive, picking up the absolutely smallest pieces of metal, and often far to small to be identifiable. In future the researcher should try to up the elimination level to exclude the smallest of fragments. Picking up every minute piece meant many attempts to find the object failed to do so, as it was often so small as to be indistinguishable from the smallest piece of grit, and therefore making the coverage of an area far slower. this sensitivity and high performance meant that the device was excellent for finding objects some 1m deep. To identify finds was the goal but this would mean multiple hits at different levels, and potential 20 minutes on one small spot, meaning coverage was extremely slow.

6. The attempt to identify finds at varied depths in the soil and record them as such did not seem to work well, perhaps because of the intent to cover more ground and the difficulties presented by identifying multiple hits at different depths at the same time. It was decided to record such detail only if items of archaeological or potential value appeared.

7. Different soil compositions provide different problems for metal detecting. There were may roots near the tree lined lake, requiring saws and clippers as well as spades, and therefore better pre-preparation.

8. The intent to have 1 researcher detecting and the other digging, or for a solo researcher to detect several hits and dig them afterwards, in an attempt to speed up the process, was abandoned after some time. It became clear once a spot was detected and the digger tried to find the item, if the object was not obvious through being small or being deeper than originally thought, then the detector needed to be employed at the same time as the digging. Even after an object was found, very often a new contact was found underneath, and then another. Therefore the detector and digger needed to be in the same spot at the same time. If there was just 1 researcher then much time was lost taking the detector on and off to start spade work. The arrangement of having the battery worn on a belt so as to lighten the weight of the detector as it swung, which could be very tiring after a while, did not work as it took some time to unhook the equipment and put it down in order to do some digging. This particular model was quite heavy in comparison to others. Even so, despite the weight factor, it worked better to have the battery on the main stem.

2020 diving survey

No finds were discovered, apart from some modern fence posts. This was due to poor visibility, as well as possible absence of archaeology. The areas closest to the shore were covered in autumn leaves, and the layers of silt and organic debris were some 1m or more deep. Some hits were registered but it was impossible to reach deep enough in the silt to examine them, and when it was attempted the clouds of debris made visibility impossible.

Yhteenveto:The project has provided no results. It is unclear if this means that the lake was not involved in Iron Age life or ritual as it maybe that finds hide deep in the sediment. To access these potential finds underwater would require far more intensive methods, which may be beyond what scuba divers cab provide, and in theory would require draining the lake and mechanical diggers. This is not warranted without actual significant prominent finds and considering the distance to the Iron Age cemetery. The lake will hopefully be dived again in the spring of 2021 when the sediments will be more settled.Lähteet:VILUSENHARJU CEMETARY. Site ID no. 837010023 (few direct electronic links to excavation reports available)Id http://tampere.fi/kyy/23993

Vilusenharju

Muinaisjäännöstunnus 837010023

Inventointinumero 16

See attached fimds pdf

- Sarasmo, E. 1961. Tampere Messukylä Vilusenharju. Rautakautisen kalmiston kaivaus. Unpublished excavation report, national Board of Antiquities, Helsinki.

- Esko Sarasmo kaivaus 1962 . Löydöt: KM 17208:1-500

- Esko Sarasmo & Terhi Nallinmaa-Luoto kaivaus 1971. Löydöt: KM 18556

Huomautuksia: (soraseulonta)

- Esko Sarasmo kaivaus 1961 Löydöt: KM 17208:501-683

- Jouko Räty inventointi 1971 Löydöt: KM 1882o . Huomautuksia: Räty 1971 - 1972 (29)

- KM 15175:1-2 Rautamiekka + luita

FINDS TO SOUTH OF THE LAKE, discovered in 2013

1. Kelloriipus, ID no 10000023900

Koordinaatit ETRS-TM35FIN P: 6818616 I: 333774

Kuvaus: diar. KM 42125.

TRS-TM35FIN P: 6818715 I: 333765

YKJ P: 6821576 I: 3333868

ETRS89/WGS84 Lat: 61,46638162° Lon: 23,87978192°

ETRS89/WGS84 Lat: 61° 27,9829' Lon: 23° 52,7869'

ETRS89/WGS84 Lat: 61° 27' 58,9738" Lon: 23° 52' 47,2149"

2. Iron Age ring and wrist pendant (ID 1000023900)

ETRS-TM35FIN P: 6818715 I: 333765

YKJ P: 6821576 I: 3333868

ETRS89/WGS84 Lat: 61,46638162° Lon: 23,87978192°

ETRS89/WGS84 Lat: 61° 27,9829' Lon: 23° 52,7869'

ETRS89/WGS84 Lat: 61° 27' 58,9738" Lon: 23° 52' 47,2149"

Löydöt:There were numerous metal hits with the metal detector, all of which were investigated. Many of these found very small and unidentifiable metal fragments. No organic finds were discovered. There were no items found of archaeological value. The finds constituted many iron nails, a large piece of metal fencing which was not recovered, a metal hinge of modern design, which looked like it came from a fence or gate, a metal clip, and a strip bracket. All these were rusted and discoloured, having been found in the peat soil. There were pieces of concrete, perhaps as part of infilling for the path constructed recently, or its curves possibly indicate some form of drainage piping.See attached Word file.

Arkeologiset kohteet

-

Tunnuskuva Kunta Vanha kunta Nimi Kylä Kaupunginosa Muinaisjäännöstunnus Muinaisjäännöstyyppi Laji Ajoitus

AvaaTampere

Vilusenharju Messukylä/Haihara

837010023 hautapaikat

rautakautinen

Jaa

Facebookissa

Jaa

Facebookissa